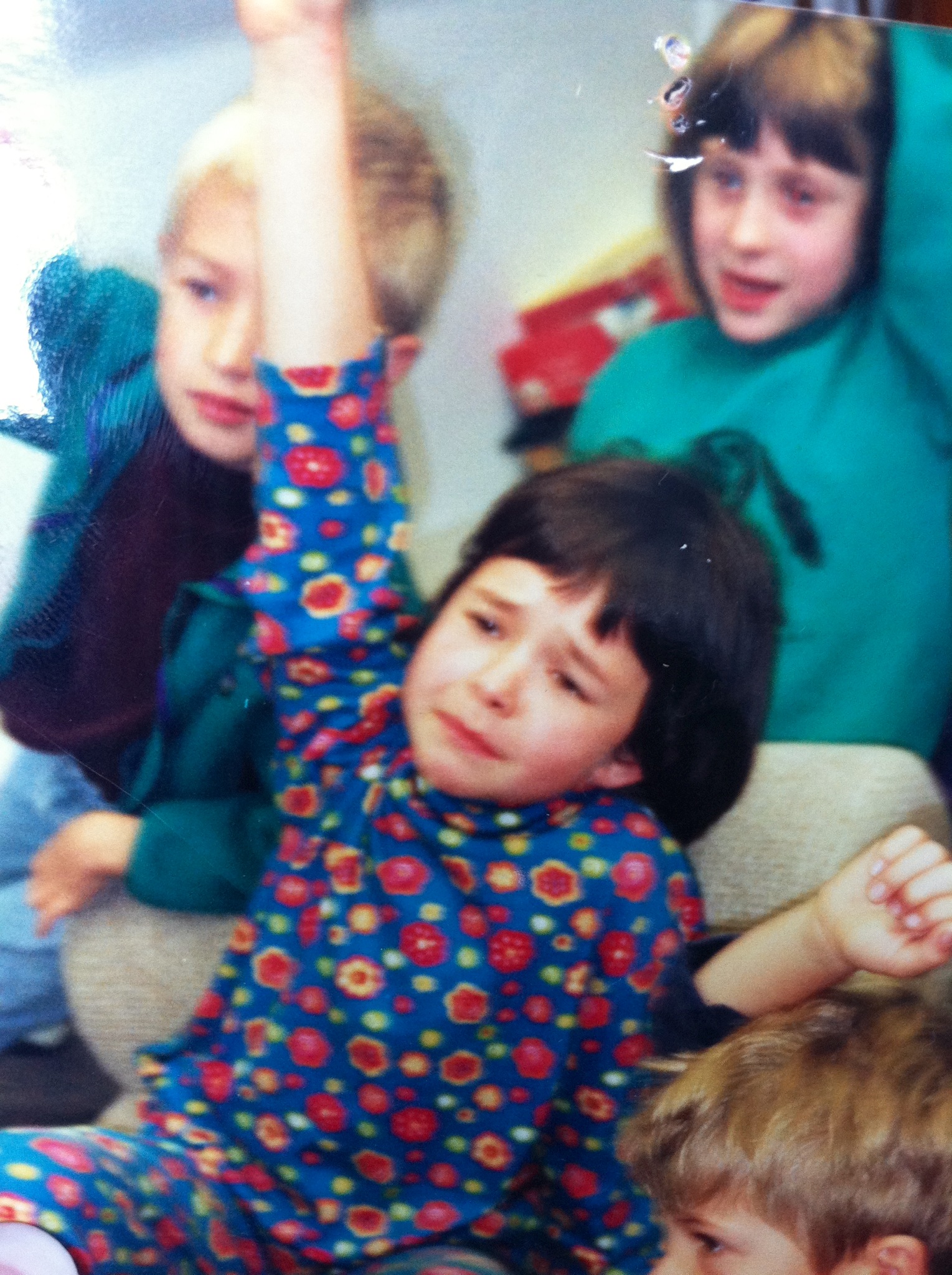

My daughter in 2nd grade in an agony of desperate excitement. “Pick me!” One of my favorite photos of all time.

Small hands wave in the air. “Pick me, pick me!” they seem to say. They are attached to little humans whose faces bear expressions of anguish combined with hope combined with glee.

They want to volunteer for the job. Whatever the job is—they want it. Little children in school long to lead the line of students to the music room or clear off the lunch table or clean the paint brushes. In homes across the world, tiny people beg to perform the tasks of life, from feeding the cat to collecting the mail.

I remember my children hovering in the kitchen as I cooked, cleaned or did something else that, for me, was a chore. “Do you want to put the silverware away?” I’d ask my 3 year old son as I unloaded the dishwasher. Picking which stack to place a fork, knife or spoon in was probably fun for him and likely a good exercise for his developing sorting skills. Luckily he was tall for his age and could peer into the drawer without a boost.

My kids would sit with me on the giant family bed amidst drifts of clean laundry. They sorted socks, folded daddy’s boxers into tiny squares and sorted clothes into teetering piles according to family member.

They loved picking up the Brio trains or wooden blocks and putting them in their baskets, especially if we sang a clean-up song.

Fast forward. Age12. Even the most conscientious child who does her own homework the minute she gets home is likely to balk at any “chore” seen as unconnected to her own immediate self-interest, no matter how-up many clean-up songs are sung.

At the school where I taught for many years, I saw the same phenomenon over and over again.

Why does taking responsibility stop being fun? Or maybe it’s not responsibility per se, but the “jobs of life” that engage and enchant us at first, and then lose their luster.

Eventually, we get past adolescence and take on jobs galore, once again willing to shoulder worldly tasks. However, we no longer leap around gleefully begging to be given more duties at work or home; we simply accept that it is our lot in life to do so.

There are exceptions to this general trend. When a young person is starting out in her own job for the first time, or when someone branches out on his own to launch a business. The new employee makes everyone else look bad, volunteering for more and more responsibilities and joyfully staying at the office until 9 at night. Everyone else may be staying till 9 too, but with a seriously different attitude. They may feel like martyrs, or just abused, or maybe get a hit of self-esteem from the superiority of it all. But that new employee, like an entrepreneur starting up on her own, is steeped in glee to be doing it. All of it.

Of course there are twenty-somethings who play Halo in their parents’ basements and don’t want to do much of anything yet. There are people who have been in their jobs for 30 years and take on every day as if they were kindergarteners hoping to be allowed to clap the erasers (or whatever the electronic equivalent of that is these days).

But I’m talking about that thing that seems to be so inherent in little kids, and in all of us when we are starting out, or starting something new. That desire to do it all, and “be grown-ups” – prove ourselves? Take on what has been forbidden until this moment?

Is it an addiction to newness? Is it simply the lack of burn-out?

The little girl waving her hand in the air, longing to be called upon to read the weather to the class feels alive as she stands up to do her job. The new teacher feels alive as he works late into the night planning a lesson on westward expansion. The entrepreneur with a great idea feels alive as she goes days without sleeping to formulate her business plan, create her website and design her logo.

I have no idea where to go with this ramble. I know there is a way to approach every day as if it were new, full of promise and possibility, a chance to make a mark, change a life, forge an identity. I don’t want children to lose that feeling so that when they are 12 years old they look at the kindergarteners begging to serve the lunch as if they are freaks. Or so that when the 40 year veteran sees the new employee bursting at the seams, he does not default to resentment at worst, exhausted bemusement at best.

Who knows? Maybe at some point we stop believing that what we do has meaning, or that we are making a difference. But every 5 year old understands that the smallest task, from being line leader to setting the table for dinner, is meaningful and important. The child who brings in the mail or feeds the cat is making a difference. Every moment and every task, every responsibility and every silly item on the day’s list will certainly be appreciated by someone, and carried out with gratitude and joy if we can look at it through the eyes of a child.