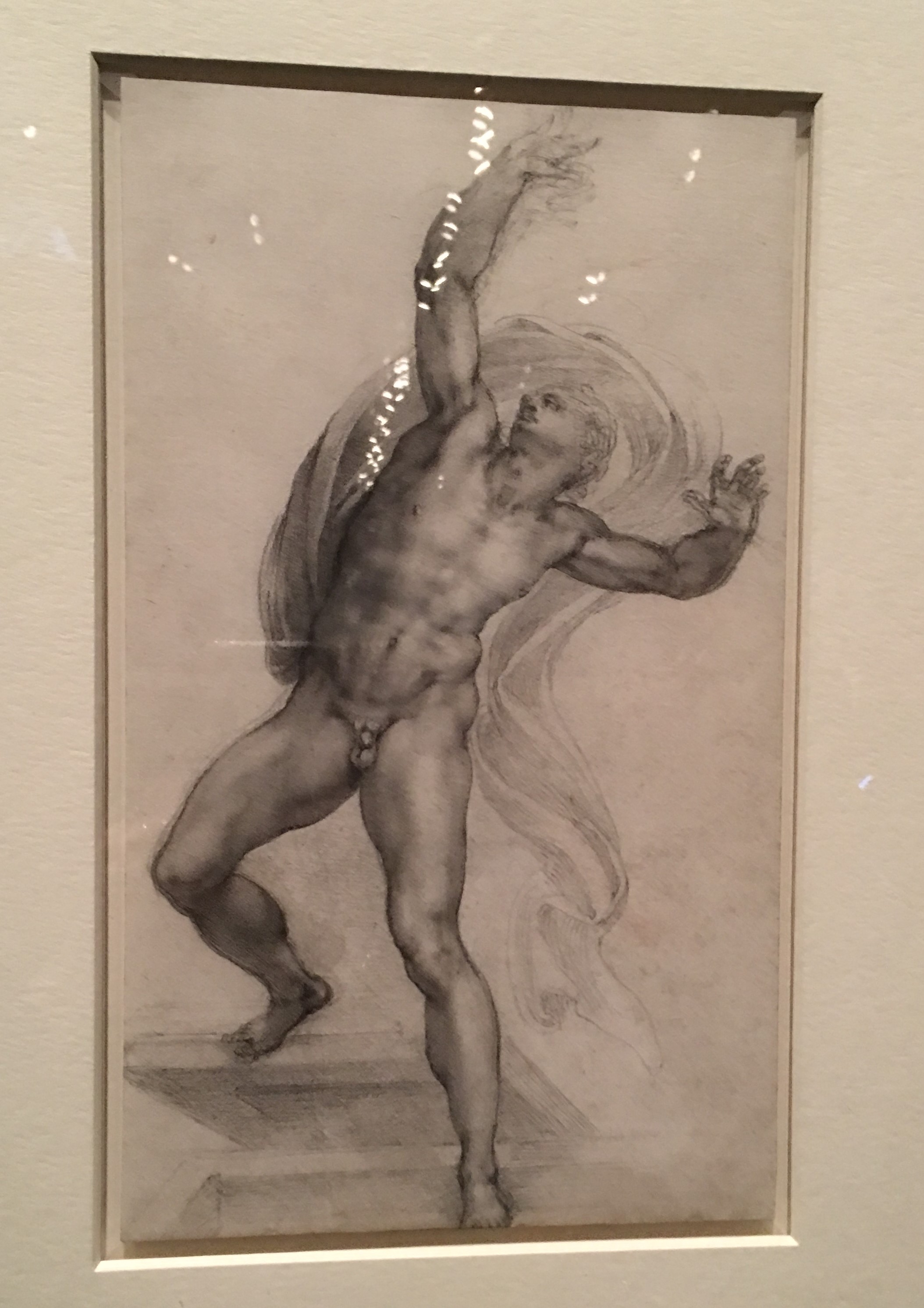

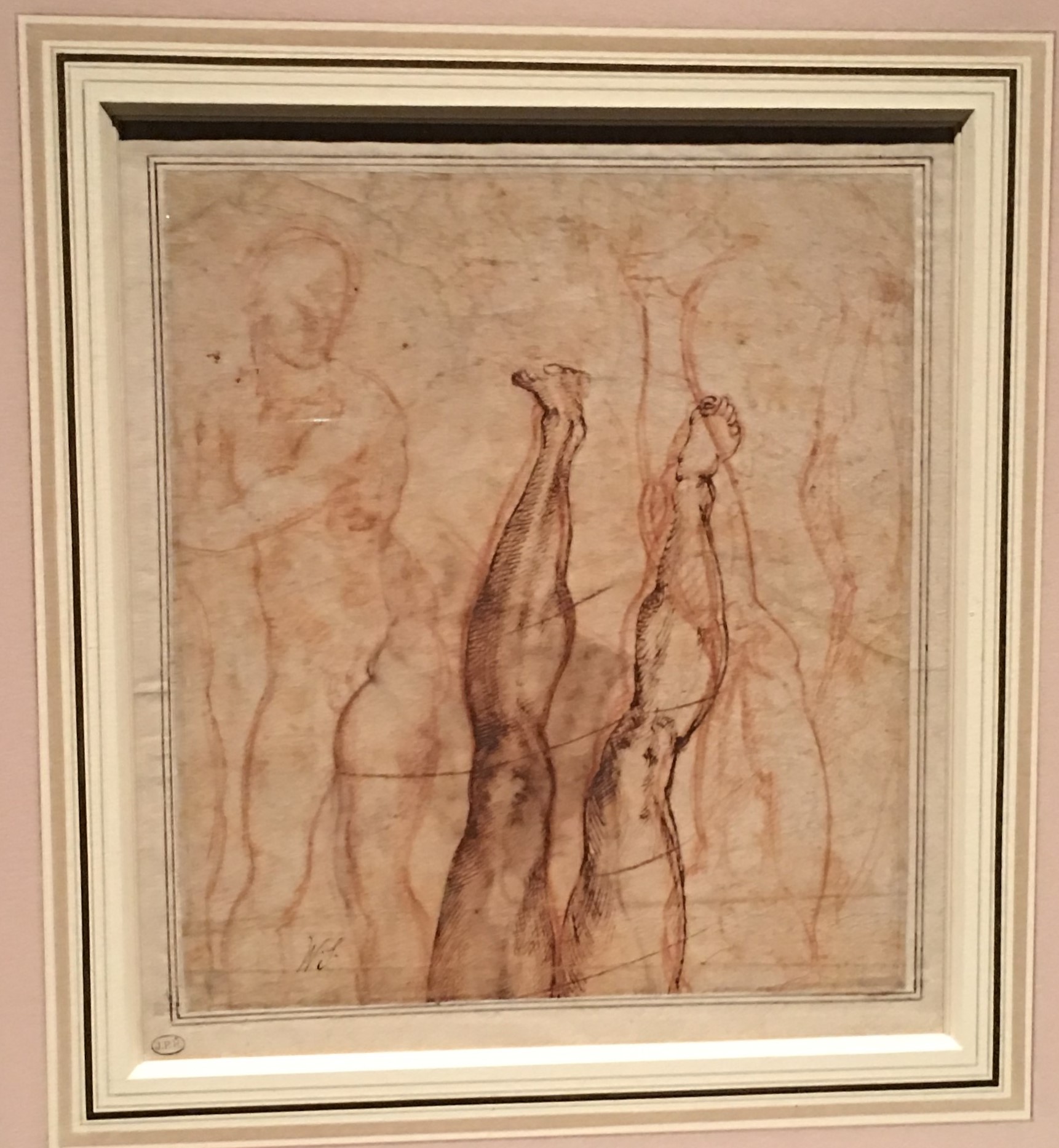

These sketches for God’s outreached hand in his creation of Adam, for the Sistine Ceiling literally stopped my heart. For a sec.

Every line, cross-out, hatch mark, smudge, and masterful stroke was made by him. Michelangelo. Himself. Il Divino—the Divine One. 133 drawings di sua mano—by his hand. Awareness of that translated into a constant ball of excitement and emotion swirling inside me.

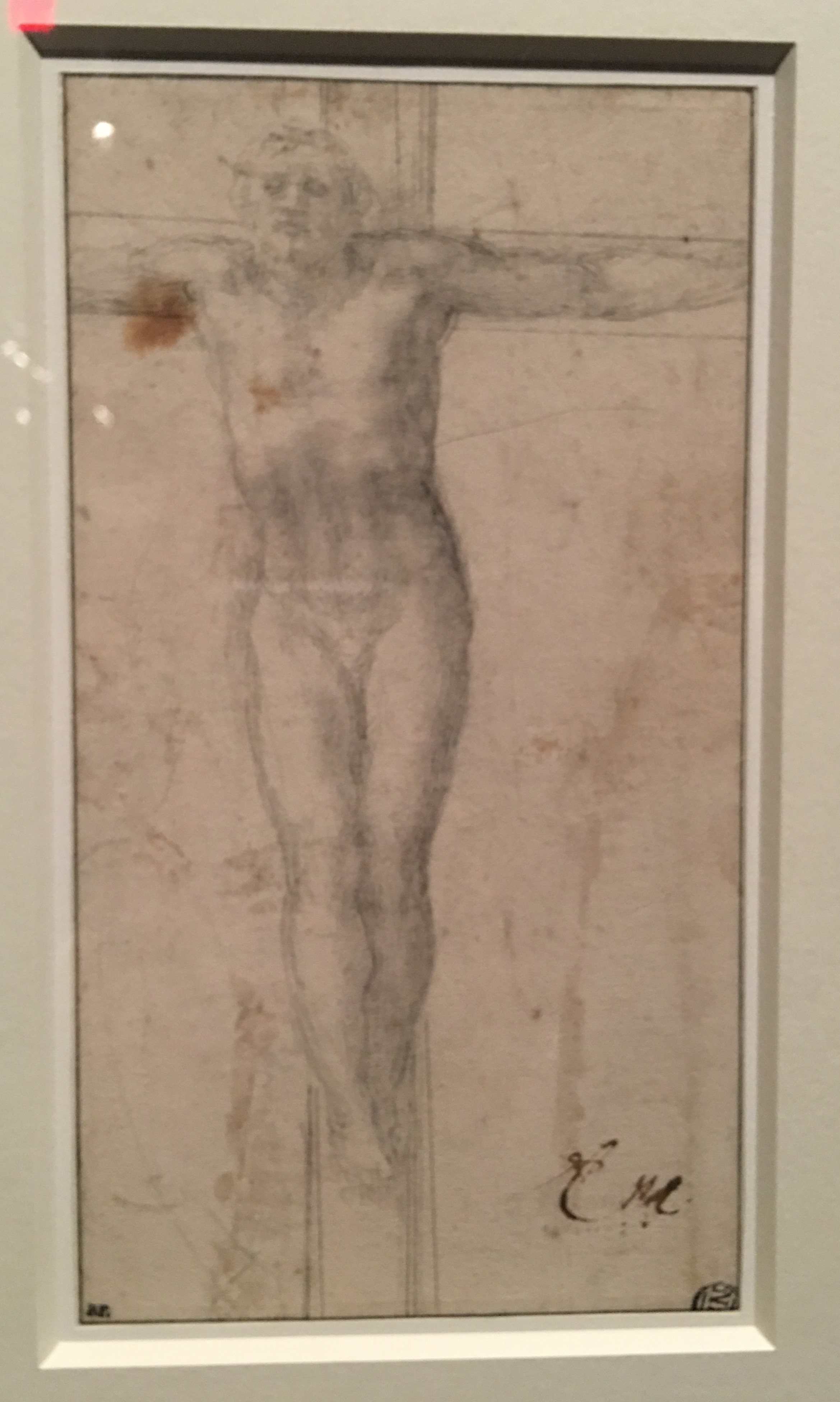

This shows how he sketched over old versions. Here the rejected then final sketches of legs for the sculpture Christ the Redeemer.

I’ve been a hardcore Michelangelo fangirl since I was about five and my mother (inexplicably) took me to the local Loews theater on East 86th Street to see The Agony and the Ecstasy, starring Charlton Heston as the master, and an all-star cast à la 1965, including Rex Harrison as Pope Julius II. On the face of it, the casting was absurd, but for the time it seemed only logical to put the most heroic of actors in the role of Michelangelo, despite his looking more Nordic than Italian. Based on a novel by Irving Stone and highly questionable in terms of accuracy, the movie did do one thing right (as I remember it a half century later). It treated the creation of art as a heroic act and, specifically, the painting of the Sistine Ceiling (around which the action mainly takes place) as something profound and beyond remarkable—truly earth shattering in the novelty and vision of the artist, and a physically demanding task that anyone faint of heart or weak of body would struggle to do.

The movie slash book takes all kinds of liberties, but no matter. When the artist (aka Charlton Heston and his super-American accent) falls from the scaffold (never really happened) I stood up in the theater and cried out—apparently very loudly—and began to sob. Suspension of disbelief has never been a problem for me.

After that, he never left me. I would not say I became obsessed, but I was smitten. By the whole idea of it. Art. Creation. The compulsion to create. Going to the Met almost every Saturday of my childhood was not a mother-driven activity as much as mother-suggested and daughter-approved. Heartily.

Throughout my childhood I read as many biographies of Michelangelo as existed in my school libraries—first the lower school library when I recall being biography obsessed in general in about third grade, then later in the upper school library where things got pretty serious. As soon as I could take art history classes in high school I was there. Then college, of course, though I did not major in it. I think my passion for the art of Michelangelo was a huge part of what guided me to take those classes and I have never looked back. My love for visual art has been a mainstay of my soul and life ever since.

Queen of Egypt. Rare finished drawing of a woman who is not Mary. Her nobility of spirit is evident as the asp bites her breast.

It occurs to me now that my longing to visit Italy may have begun with my love affair with this artist. Since then, I’ve accrued any number of brilliant reasons to travel to that country (almost all of them related to various artists, artworks, architectural masterpieces, and then there’s the food), and will do so before I hit 60 (my vow to myself).

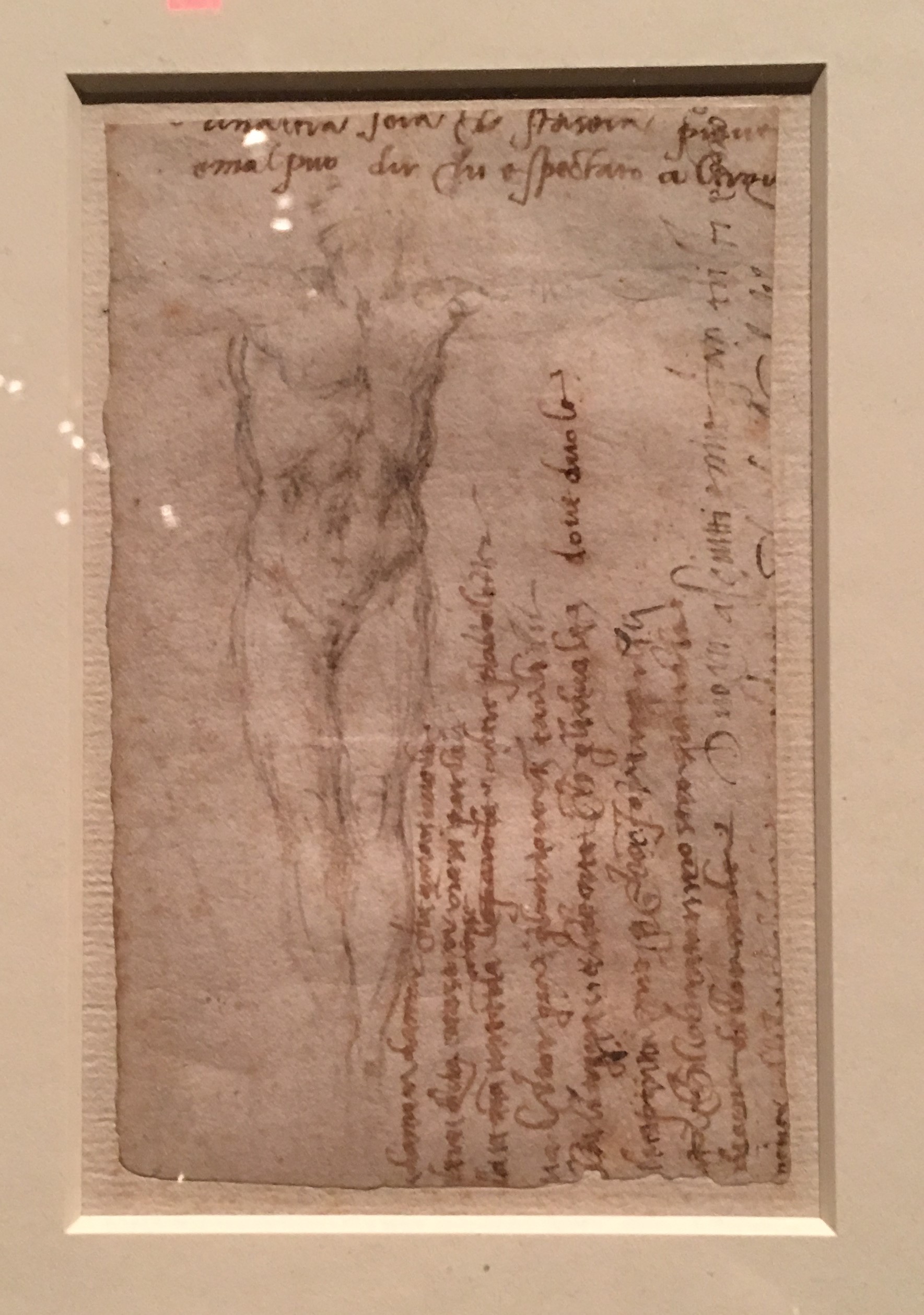

Sketch of a leg for a figure in the Resurrection scene in the Last Judgment. Added later: a snippet of a madrigal he wrote about being tortured by flirtatious eyes.

In addition to the 133 drawings, the exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, called Divine Draftsman and Designer, contains two sculptures, a small reproduction of the Ceiling in glass overhead in one gallery (drawings/cartoons of some of the figures are exhibited below), and a great deal of top notch curatorial information to read in every room, something one can count on at the Met.

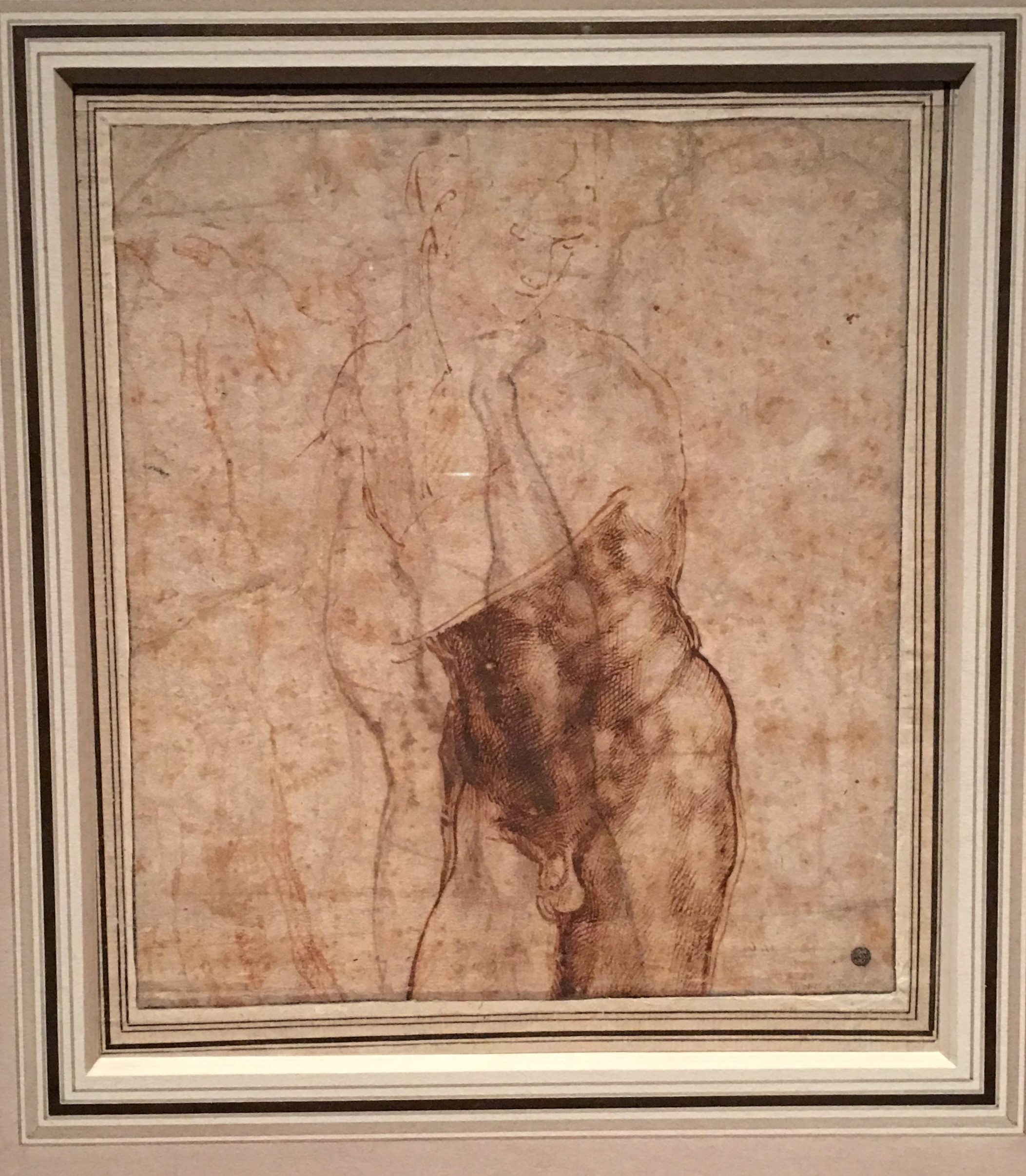

Study for the sculpture of the reclining figure of Night for the Sacristy of San Lorenzo. Leg and shoulder are all that are finished–the rest sketched in.

The first two rooms were so packed that movement was nearly impossible. It was more of a gradual ooze of bodies that, if I was lucky, would take me near enough to the art that I could see it. Eventually, the crowds thinned comfortably enough so that getting a chance to gaze at every piece was a guarantee. (I think people gave up. I would never give up.)

Study for Virgin and Child sculpture. Toddler Christ astride her leg, twisted and nursing. The figure of Joseph suggested in back.

Almost immediately when I got to the second room—the first was full of great art by people who inspired and influenced Michelangelo—I felt the rush of emotion and overwhelm hit me. Looking at a drawing—red chalk on a piece of paper he had used before (never wasteful, my frugal hero)—the awareness bloomed inside me. He touched this. He made this. His radical, confident vision manifested on this paper. Tears sprang to my eyes (if you know me or have read my blog you realize I react to strong emotion this way). They leaked out and I stood like a fangirl fool swiping at my face in the middle of a mob of art admirers. No one noticed, of course. No one could tear their eyes from the work. Who could?

I’m no art critic so this blog won’t tell you how and why, nor even what. My only intention is to share with you, anonymous reader, my sense of joyful fulfillment at being in all those rooms with all those drawings. Many of them were displayed in the middle of the room so we could see what he drew on both sides. He often did that. The sheer volume, and the sheer range of subjects, and the way he often revisited the same figure or movement or scene in a second, or even third drawing—all of it “tasted like more,” as my grandma used to say.

Unfinished cartoon of Virgin with Child. In characteristic fashion, orso and arm finished to a high polish–the rest rather impressionistic.

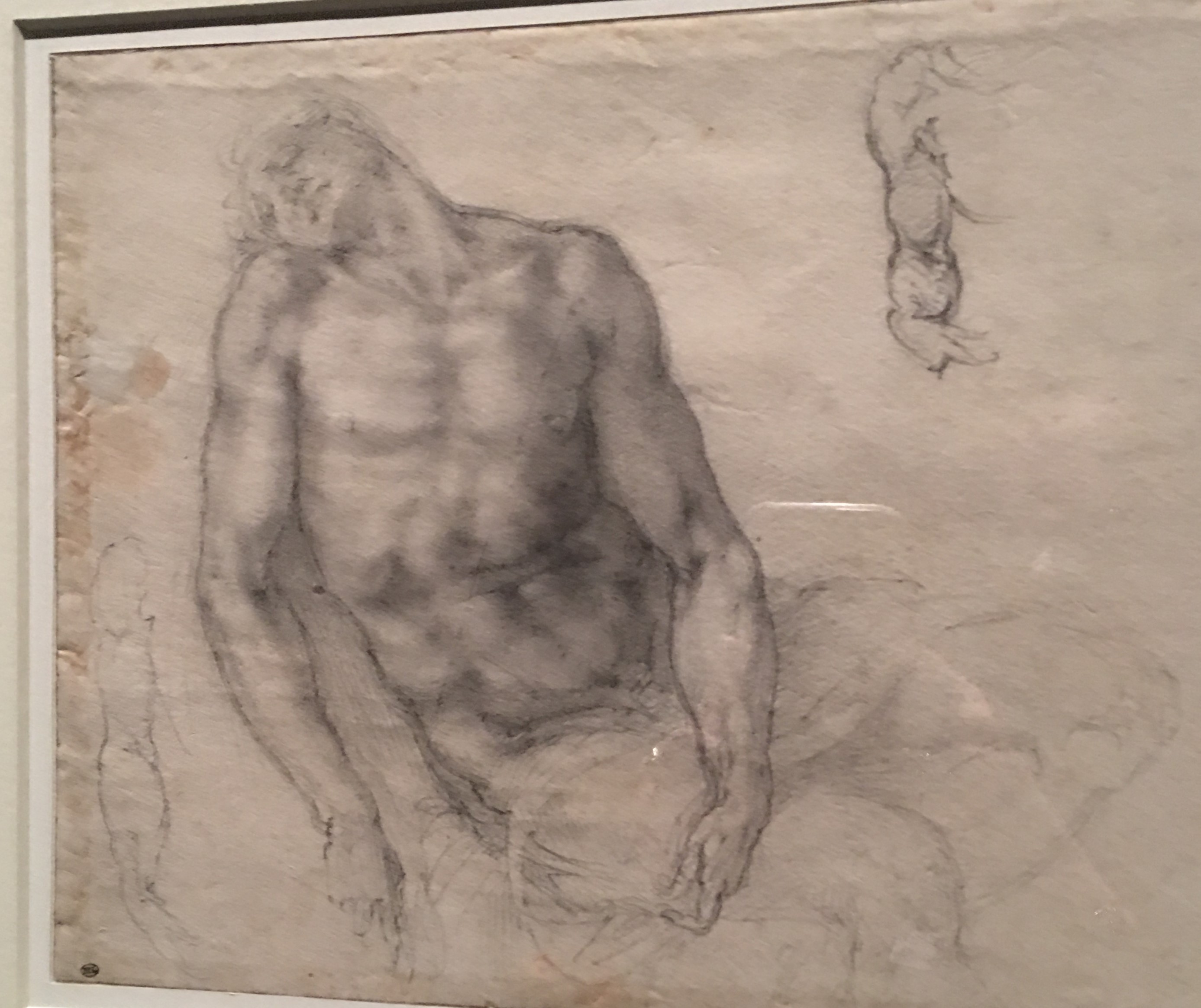

His famous technique of finishing one detail or section of the form while leaving other parts sketched-in, suggested, was suddenly very real to me. His passion for the human form, mostly male, his profound piety and devotion to Christ and Mary, his incredible mastery of all art forms (from drawing human forms to architectural details to full-on architectural designs, and the thing he most valued, sculpture). And his passion for writing (sonnets, for example)—all this was all there in front of me, made manifest di sua mano.

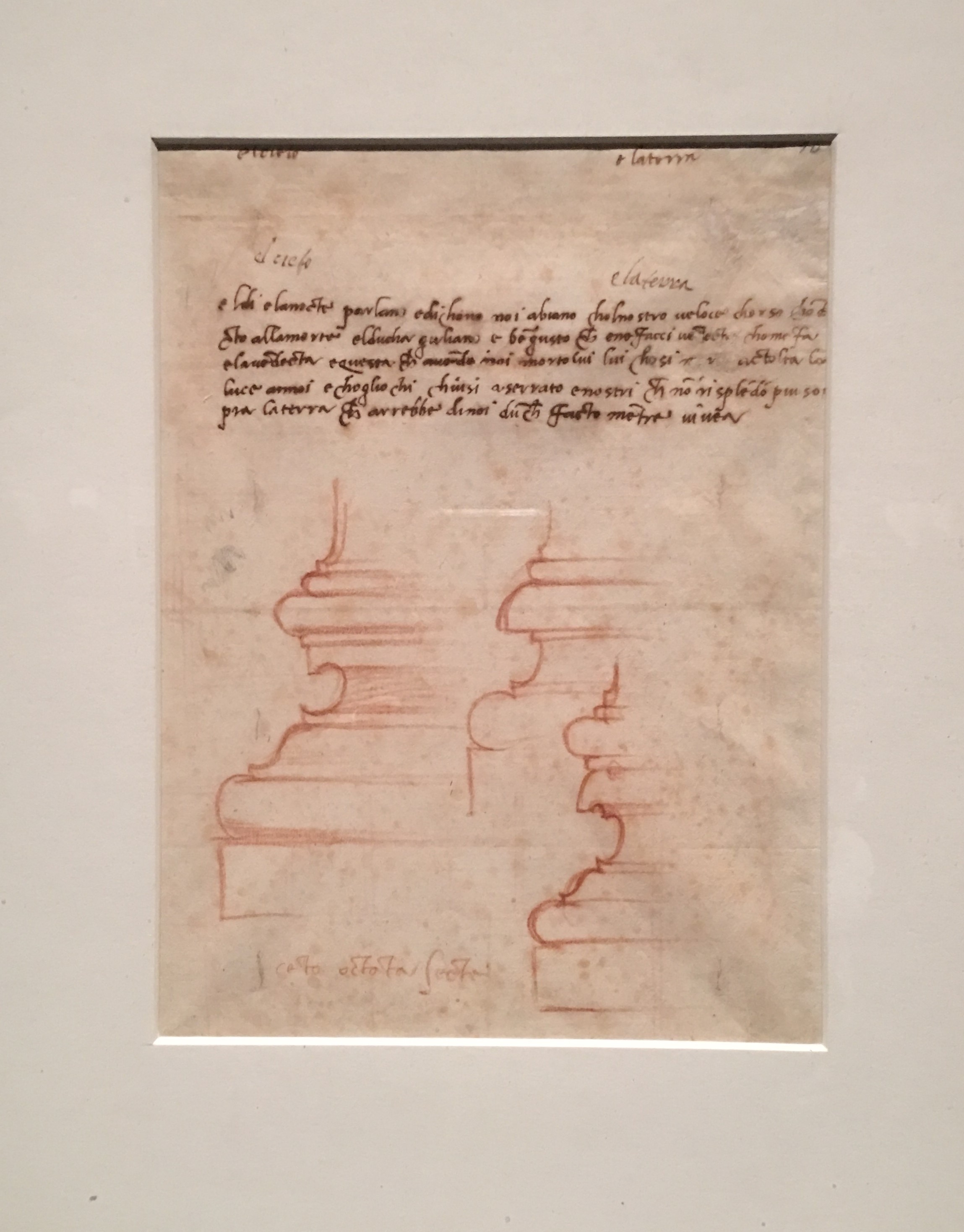

On one sheet, in among the others, he had sketched some architectural details, “revealing the artist’s process of vivifying inert forms”*. (Yes, he did that. Somehow.) Below that, he had, for his own amusement, lightly drawn a screaming man, in profile. At the top of the page, unrelated to the rest, a few lines in his glorious script, jotted down straight out of his mind, ever active, curious, creative. A dialogue about death, between (obviously) Day and Night.

Study for the second version of Christ the Redeemer. Again, detailed section with the rest hinted at. The figure’s S curve is a signature of his too.

I stared at this for a very long time. I fell in love all over again with this human who walked the earth 500 years ago. Very much a human, but divine nonetheless, as only humans can be, of course. Divinely inspired to create, change the world, express his vision, recreate reality itself. Like other great artists, his impulse to create and make was never about me or us or anyone who bathes her or his soul in the things created. It was an imperative. Sure, he took commissions and did jobs for people who paid. A man’s gotta eat. But, commission or not, it was clear that these drawings were done by him, for him. Because.

Design for the staircase of Laurentian library came to him in a dream. He drew over the earlier drawings of a pupil.

Studies for the Pieta of Ubeda altarpiece. Christ’s limp right arm sketched three times. Finished sections contrasted with suggested sections.

*credit to whatever Met employee wrote the text for this exhibit