For years I was steeled for her death. I never knew, when the phone rang, if it would be news that she had died, alone in some city, or if hers would be the voice I’d hear. Either the harsh accusations or the begging born of anguished paranoia. The urgent instructions to call this corporate giant or that estranged relative in order to vindicate her once and for all. Sometimes it was the kind of call that ran the gamut from invective, to sobbing desperation, to sinuous manipulation. I was to drive 400 miles, tonight, and take her home to live with me, in her rightful place, because surely, I owed her that. Didn’t I owe her my life? She never hesitated to remind me. And the gift of life meant I owed her everything she could demand of me, any sacrifice, my family, my job, my very self.

The manipulation-through-guilt was always hardest to take. I had spent most of my life, even as a tiny child, believing that her fate was somehow in my hands, and that any unhappiness, or dissatisfaction or mere discomfort was somehow about me: my fault. If only I could do just the right thing I could fix it. I alone could keep her from falling into the subway’s path. I alone could keep her from loneliness late at night when her work was done. So, as an adult, I had to live day to day knowing that she was miserable beyond my own conception of misery, and that there was nothing I could do about it. The darkness in her mind made a reality that was almost too much for me to think about. Years of therapy eased me to the brink of understanding that I could not protect her, and harder yet to believe, that I never could. I certainly could not keep her alive when half the time I had no idea where she was. And besides, she was consumed by madness, totally lost in her own irrational maze cluttered, it seemed, with doors she could slam, but absolutely no exits. As a grown daughter, uncertainty and helplessness defined my role. However, I believed I was prepared, at least, for news of her death.

The five years that she was back in my world, living peacefully and safely, medicated and fairly stable, were so much better. She was back where I could see and touch her. At least a version of her had returned. But she was not really identifiable as the mother of my childhood. The spark and the laughter were gone. The need was huge. Her fears had abated to simmer just below the surface. We could “chat,” and stroll through Wal-Mart shopping for blouses and selecting underwear with an invisible panty-line. Each time I picked her up to go have coffee, or stop at CVS for moisturizer, she always made a point of asking about Dan and the children. Because she had missed 20 years of news, I spent some time filling her in about the state of the world. She had missed the presidencies of Bush Sr. and Clinton. She did not recall ever hearing the term “gay rights,” nor did she realize the rainforest was at risk. She asked innocent, childlike questions. She thought Republicans still stood for small government. The state of things confused her. Our roles had fully reversed. I worried about her living situation and worked to develop a rapport with the staff at the two assisted living facilities where she lived during that time.

Meanwhile, I ached to actually look forward to our visits. I wanted desperately to love our time together, but the time was painful, a chore, a fact which in turn haunted me with guilt. She demanded much and gave little in return. Unlike a child, whose delight in life fills your heart even as you do and do and do for them, my mother’s primary emotion was dissatisfaction, seconded only by deep sorrow. She mourned things she knew she’d lost and even things she could not remember ever having. All she knew was that her life was empty. I felt the terrible burden of being the only thing to fill it.

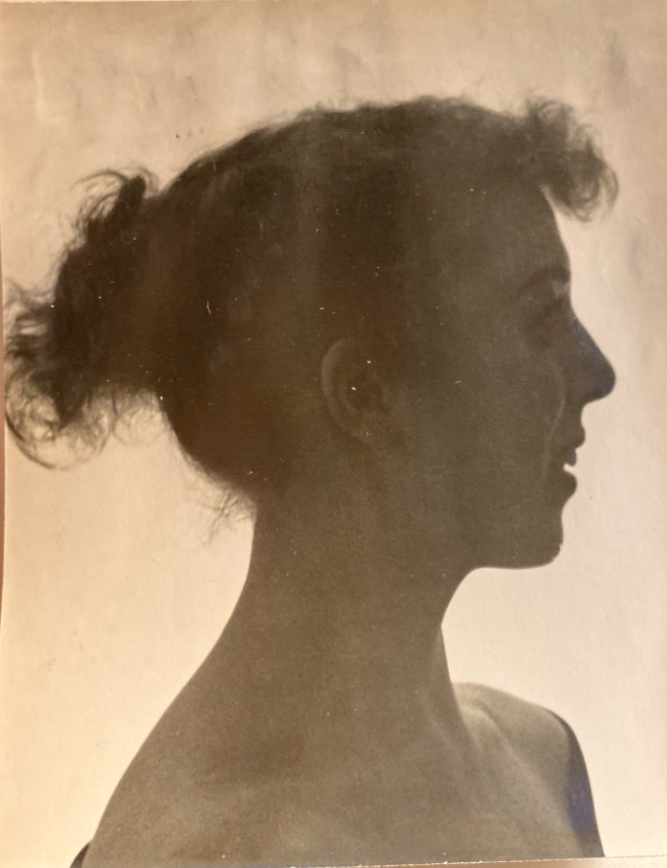

At this point, my preparedness for her death waned. I became sure that she’d outlive people decades older than she. Her mind was unstable, but her body, as always, was strong. And now that she was housed, fed, saw the doctor, what would stand in the way of the tremendous longevity I imagined? The weeks and months and years passed. My life was full and busy and rich; my children grew, my job fulfilled me, my husband loved me and completed the circle of our family. On the edges, never quite knowing how to be included, was my mother, who really wanted only me. The sight of me pricked her longing for the way things used to be. She saw in me her only hope of recapturing the past, her glorious past when she was beautiful, strong, lucid, admired, and had a trophy daughter worthy of her. The life I now lived, as mommy, wife and schoolteacher, did not fit her dream vision. She tried to care about it but couldn’t really. She dutifully asked about me, my job, my family. She enjoyed hearing tales of my children’s brilliance and accomplishments, because she could be reminded of when I was a brilliant and accomplished child. But always it was me, and only me, that she wanted. For my part, I was willing, glad really, to tether her to life, be her tie to any shred of happiness or pleasure. I imagined this role carrying me into my sixties, long after my children left home and into a time when I could give her more of myself, as she aged.

But all that changed. Despite a move from a brief but unpleasant assisted living situation to a warm and supportive nursing home in Great Barrington, she sank deeper into depression. At that point, even I was hard pressed to provide her with so much as a glimmer of pleasure. Enjoyment of any kind was out of her reach. She was withdrawing further and further into a death in life, as she spent every minute of every day lying in a dark room on her bed, her cardigan pulled up over her shoulders. Her dignity, you see, never faded. She would not allow herself to languish in her nightgown, under the covers all day. She got up, dressed, combed her hair, dabbed some mascara onto her pale lashes, and lay back down on top of the made bed to doze her life away in the cradle of deep depression. And then she got sick.

Her hospitalization and emergency surgery just after Christmas brought her quickly to the brink of death. Post-surgical pneumonia prompted the doctors to call me at work to ask for a suspension of her DNR order. They believed that she could come through this infection with treatment. What do you want to do? If we don’t intubate, she will die. Soon.

I wasn’t ready. I was pretty sure she wasn’t ready. She and I had spoken several years before, when she prepared her living will. She said then that she did not want a life on machines, but she was also living in the artificial world of her own mind, and I don’t think she believed in the inevitability of her own death.

And anyway, this was different. She could come through this. And I still did not know the results of the lab tests on the mass removed from her colon. We had no real diagnosis. I stood in the hallway outside my classroom, the phone cord stretched taut, and cried to the doctors: “Am I condemning her or saving her? Can she live?” I suspended the DNR and rushed to Pittsfield to see her.

There she lay in the ICU, a frail, pale woman breathing on a machine, an innocent Vader, with air pumped in and out on a timer. She was, essentially, not there. She could barely register my existence. If this was going to be goodbye, it sucked. There it was again. The guilt. It was at this point that the surgeon finally told me the lab results: cancer. The massive tumor he had removed from her colon was as malignant as they come. If she lived through this pneumonia, what would she face? Another kind of death, this one slow and painful? But would we both be ready then?

Three days in the ICU on penicillin and her pneumonia was cured. She was healing amazingly well from the abdominal surgery. She got out of the ICU and within 3 hours was making me laugh. Who was this woman? She was drugged and in pain, exhausted and confused, so her witty comeback to a comment I made to the nurse stunned me. Not to mention the fact that she had neither laughed at my amusing comments nor made any of her own for over 20 years.

Back at the nursing home, she was a woman reborn. Though fragile and thin, with no appetite for food, suddenly my mother found her appetite for life and experience. She sat up in bed and eagerly visited when I came. She began to tell stories of her childhood and share memories of mine. My children came to see her and it was as if they were meeting their grandmother for the first time. My youngest, Maggie, listened to stories of the horses on the Bauman farm, and tales of the retired polo pony, Johnny-Boy. Maggie was delighted with this new grandmother with horsey stories to tell. As we left the room at the end of that first post-near-death visit, Maggie took my hand and said, “Mommy, she’s nice.”

I had a mother. I wasn’t sure how I’d gotten her, but there she was. She had complete amnesia about all the years of hardship, vitriol, anger, anguish, sorrow, and emptiness. Her forgetfulness sparked in me an ability to live only in the present, with this woman who was my mother, and memories of a mother I once had, and to forget the madwoman who haunted so much of my adult life. This mother did not make impossible demands. My desire to do whatever I could for her increased with every passing day.

Somehow, I recognized this woman. Once luscious and full breasted, she had become skeletally frail. On the once beautiful face, her gaunt smile had become a rictus. Her touch on my skin was cold. And yet, she was familiar. I felt like a daughter again. And I remembered something. I loved her. Even though I’d been saying the words to her for years, they had always made me sad.

Last year, as I watched my mother’s rebirth and death, my love for her tapped me on the shoulder and said, I’m still here, you know. That love, it must have been standing in my blind spot for a time.

I had about a month before she began the active process of dying. Although she could not fathom it, her days were numbered. She barely ate, and finally, with permission and the advent of hospice, stopped altogether. It was only a matter of time. I thought: I am not ready, but I can be. I believed that I only needed some time. Time with her. Time to part. To help her leave. To forgive her. To forgive myself. To love us both enough to say goodbye.

Take it from me. We’re never ready. But the parting is still important. I crammed 20 years of togetherness into a 12-day bedside vigil. I never tired. Never chafed. I could not bring myself to leave her side. Every tender massage of her feet or hands was an opportunity for me. Every offer of a sip of juice was a way of loving her. The music I played for her, well, it made me feel better anyway.

My world shrank to a 15 square foot space. Once again, as we had for the first 12 years of my life, we shared a room. Two twin beds, mother and daughter.

My few childhood memories of my mother as a nurturer are from when I was sick, my skin hot, my throat sore. Even though she had to go to work during the day, when she came home, she sat beside me and laid her hand, cool from the winter air outside, on my face. This time, in her last days, it was my hand on her brow. My soothing talk, her restless sleep. My bustling, her gratitude.

I lived every day of those last weeks in a state of awe. Every sense was tuned. When we bathed her body, childlike in its state of starvation, its beauty made me cry. Her skin, like silk flowers, encased her once strong bones. Her face, smooth-skinned even at 75, could occupy my eyes for hours. Much of the time I sat and read or read student essays or recited memories. Many hours passed without my being aware of what had transpired.

I watched her watching the guest who spent those final days in the room with us, invisible to all but my mother. She stared fixedly at a spot beyond me, murmured, “I need more time,” and yet reached out her arms. She kept a vigil just as I did. She seemed never to sleep. At other times, she watched me intently. We exchanged gazes.

Though she did not have enough fluid with which to make tears, I soaked the pillow by her head as I lay my face beside hers and grieved. In those last days, my mother gave me the gift of her mothering. Although she was busy strong-arming death to gain another hour or day of life, she found the wherewithal to wrap her bony arm around me as I cried on the pillow, to stroke my hair, to gentle me towards her eventual, regrettable leaving.

I yearned to crawl into the bed with her and wrap her up with my body, hold her and ease her way, but I couldn’t. She was so aching and sore in the last days that she could not tolerate any touch but the brush of my lips on her brow, or my open palm cushioning her hand.

She lived seven days past the day the nurses said she could not possibly make it another 24 hours. During those timeless days, I forgave her and asked for her forgiveness. I told her I would write about her. I told her I loved her. I said, “Give my love to Aunt Thelma and Uncle Mike.” I told her she could go. I told her she had to let herself go. I said, “Don’t worry about me. I’ll see you again.”

She waited till Dan could be with me before she took her last breath. She had teased me, though, into believing that though she was dying, she would never really die. I was in the bathroom, washing up, when Dan called out, “Vanessa, I think this is it.” I rushed to her bed. She was staring, wide eyed, right at me. The quiet in the room was deafening. The strained sound of her breathing, the accompaniment to my days and nights, was agonizingly, horribly silenced. After weeks of watching her inch her way out the door of life, when the door finally closed behind her, I was left absolutely stunned and bereft. “Is this really the way it is? Is she gone?” I wailed. Her leaving was so permanent; a trapdoor opened in my chest. But: she was still there with me. I could feel her beside me, around me, waiting for my last goodbye.

At last, I could crawl under the covers with her, wrap her in my arms and hold that body one last time. The one that gave me life. I owed that to myself.

The preceding was written in 2005, on the first anniversary of my mother’s death.