It has been a long 4+ years since I posted on my beloved SpiralWoman blog. I will not even try to explain why, mostly because it’s a combination of such complex reasons that I don’t really understand it fully myself. I am going to start posting again. Different material entirely. Instead of personal blogs and dives into my wide-ranging areas of passion, concern, or love, I will be posting sections of a book I’m working on. A memoir written by a woman who has an extremely spotty memory of her life. I am experimenting with an approach that is episodic, multi-genre, and in some instances actual short stories or semi-fictionalized narratives based on a combination of my own memory, research into my life, research into the life of my mother, and my imagination. Most of what I post will not necessarily be sequential so even if you have not read the last entry, you will be able to understand and follow the next. These entries are distinctly first drafts so read accordingly. I am eager for feedback if you are inclined to provide it. No expectations, however.

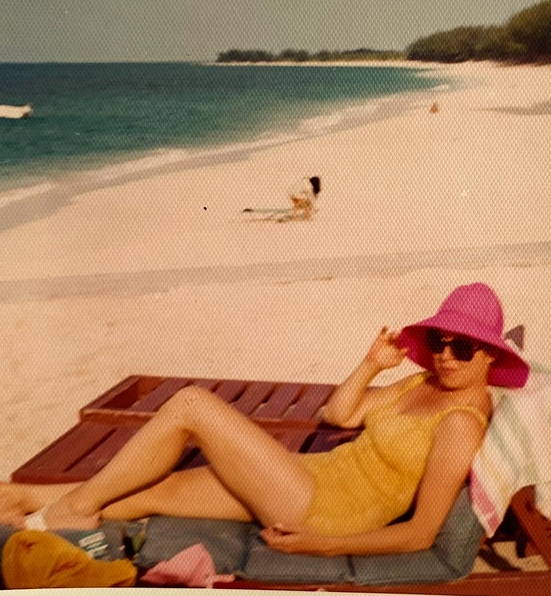

I have selected the following “chapter” at random from my ever-growing folder of pieces that will ultimately (probably) end up in the book. Hoping to post weekly. Thanks for reading. The photo below was taken when she was probably in her 40s, maybe by me (she once took me with her to the Bahamas on a business trip).

The Pick-Up and Drop-Off

She had agreed to take her meds, so the hospital agreed to release her. I had learned to take nothing at face value and was absolutely sure that she had no intention of taking her meds.

Until the day she died, she never admitted she was ill. According to my mother, her only problem was everyone else in the known universe—and their commitment to sabotaging her until there was nothing left of her life.

It was Valentine’s weekend. My husband, toddler son, and baby daughter drove down with me from New York. As my mother’s next of kin, I was to receive her. I left my husband and children at Grandpa’s house in Northern Virginia and drove up to the Springfield Hospital Center in Maryland.

Passing through a series of locked doors, I arrived in her ward. Tooth enamel white walls gleamed under dozens of fluorescent lights. The nurse’s station was behind glass with lockable doors. Just in case.

She was waiting at the back of the room, nearly dwarfed by an enormous suitcase and dressed in immaculate cornflower blue jeans and a crisp white blouse. Later, I saw that the neck of the blouse showed signs of fraying and there was a circular brown stain on the placket the size of a pencil eraser. Around her neck was a designer silk scarf—creamy beige with navy blue swirls. She might have had it for 25 years, but it looked elegant and unmarred. When she saw me, she picked up her purse. The cheap teal colored vinyl had bald spots and the gold-tone clasp was missing most of its gold. Purses get stolen more than most things when you’re homeless.

An empress in jeans, she allowed herself a tight smile when she got close and let me pull her suitcase. She walked toward the exit doors.

The nurse behind the glass spoke into a microphone. “Mrs. Lynch? Norma?”

Haughty as ever, my mother turned and looked at her. “Yes, Evelyn?”

“Mrs. Lynch you can’t leave without your medication and you and your daughter both have to sign some papers.”

“Very well,” enunciated Empress Mother.

We left the suitcase against the wall and approached the nurse’s station. Before she signed anything, she read every word of every document, glasses off, eyes two inches from the page. I watched as she signed. I never got used to her new name: Norma Lynch. Norma, the first name on her birth certificate—one that only her mother ever used. Lynch, the name of her second husband, Don.

The signature was no longer the big looping Lee Park I knew so well. This was much more straightlaced— Norma Lynch, as if a name could determine a signature. The unknowable Norma Lynch inhabited the body of my very own mother.

The nurse gave her a pharmacy bag. She shoved it into her purse, turned, and walked away. I paused and said, “Thank you, Evelyn, for your help and compassion toward my mother.”

Evelyn smiled. “Norma is God’s creature, and a unique one at that. We had a few long chats. I know for a fact she’s very proud of you.”

When I joined my mother at the door, someone pushed the unlock button and a buzzer vibrated the air. I leaned into the heavy door, and we walked out.

“You did not need to speak to that woman and there is certainly nothing to thank her for. She’s paid by my enemies to keep me here. She might not know it, but she is.”

“But you are leaving. And she was kind to you.”

“Darling, a kind jailer is still a jailer.”

My car was in the adjacent lot. I lifted her bag—it must have weighed 60 pounds—into the back seat of my car and opened the passenger door for her. We didn’t speak.

Within thirty minutes, we were driving through dusk-darkened streets looking for a parking spot.

With every block, my chest tightened with anticipated grief as my breasts swelled agonizingly with milk. Maggie had not nursed since wake-up.

I parked two blocks from the shelter. We walked in silence. I pulled the suitcase with one hand, and with the other I held my mother’s hand, as I’d done ten million times in my life. It was as warm and soft as ever. She gestured with her chin. “It’s up there. What time is it?”

“I don’t know. We left the hospital just before 5:00. It’s already dark so I bet it’s closing in on 6:00.”

“We aren’t allowed to line up until 6:30.”

How could I leave her? Just walk away from her as she paced the block dragging her suitcase, waiting for check-in time?

There was a Burger King on the corner. As soon as we entered, she pulled the medication bottle out of her purse and dropped it in the trash bin near the door. Two steps behind her, I pulled it back out.

She sat at a booth shaped out of a single piece of orange plastic while I bought two cups of coffee. I dumped the contents of five creamer pods into her cup and returned to the booth. My straight-backed mother stared ahead out the dark window, the monstrous suitcase taking up space in the narrow aisle.

She held the cup delicately between the outstretched fingers of both hands. It was such a subtle thing, but a signature of hers. A simple, delicate, oft-repeated gesture, more memorable in many ways than her former magnetism and the way she could fill a room with her personality and glow.

A digital clock on the wall said 5:56. Do I leave now, knowing she’s only across the street from the shelter? Do I wait till 6:30 and walk her to a spot in line? Exactly how do I navigate what will be less than one minute of my life? The single minute, one of so many impossible minutes. This one would be me, saying goodbye-I-love-you, kissing her cheek, and turning to walk away.

I finally said, “I need to get to Maggie soon. I’m really engorged.”

“Your place is with me. I know you don’t see it that way. You’ve made that clear enough.”

“Momma, I’m a momma now too.” She turned away, refusing to look at me, staring intently at the frail man slouched in the booth across from ours.

I reached out to take hold of her hand. She gripped mine fiercely, as if enduring awful pain and relying on me to ease it. Then she let go and withdrew her hand until it lay on her lap, below the table, inaccessible.

I looked at her face, unlined at 64, hair thin and darkening from blond to steel gray. Full lips set in a grim line. Bitter endurance had become her resting state. I put the bottle of pills on the table. She pretended not to see. I half stood to reach across and lift her shabby teal blue purse from the bench to the tabletop. Snapping open the chipped gold clasp, I dropped the bottle inside and put her bag back down beside her.

She pretended, again, not to see. I knew they’d be back in the trash the minute I was out of sight. I was shamefully grateful that she decided this time not to do battle, shout imprecations, or lunge across the table as if to wrestle me to the ground.

“Go if you have to. I’ll be fine.” She glanced at the clock. “I only have ten minutes to wait.” She was looking at me again. Her words were perfunctory, but her eyes were soft. Her mouth relaxed. Then she smiled. I could tell it cost her something, but she meant well. She felt love. She always did, somehow, when it came to me. She was being kind, in her way. Letting me go to my children was a gracious act. The daughter who chose to leave her at a homeless shelter rather than take her into her own home. The cruelty she attributed to me was a burden that pained her heart—and mine—every day. I was resigned to the fact that she’d never understand.

From inside her mind, the entire world had betrayed her, but the worst betrayal of all was mine.

As I walked to my car, my throat clamped down. In the driver’s seat, the sobs roared out of my chest. I sat like that for some minutes. Finally, as I tried to get out of the neighborhood and find a highway heading south, I did figure eights around the same two blocks a few times, and then found myself driving past the shelter. My mother was third in line, her enormous black suitcase blocking out half her body. Her gaze was fixed on the dusk-shrouded rooftops of high rises beyond her reach in more ways than one. She did not see me.

Powerful and lovely ??

(Not sure why the question marks are appearing. It was not a question, just a statement)

Sometimes punctuation volunteers itself. It’s an odd thing. And I thank you so much for reading and commenting, dear Katie! XOXOXO

Beautiful and incredibly evocative. Your writing has made me both see and feel the entire encounter. “The daughter who chose to leave her at a homeless shelter rather than take her into her own home.” WOW! That’s a powerful, emotion-packed sentence.