For a person who tends to overthink things, it’s odd that I never really examined why Sylvia Plath was such a powerful force in my teen years. Today, when Google reminded me it is her birthday, I had an intense emotional reaction to realizing that she would be only 87 now, had she lived. All the decades of her absence slammed into me as a deep loss. I feel my throat tightening again now, and the hot glitter at the edges of my eyes.

For a person who tends to overthink things, it’s odd that I never really examined why Sylvia Plath was such a powerful force in my teen years. Today, when Google reminded me it is her birthday, I had an intense emotional reaction to realizing that she would be only 87 now, had she lived. All the decades of her absence slammed into me as a deep loss. I feel my throat tightening again now, and the hot glitter at the edges of my eyes.

When I’ve told people in the past that Plath was an important writer for me, I’ve heard comments like, “Oh that’s so dark,” or “Were you suicidal too?”

What? Do people who love Byron have to be promiscuous bisexuals to adore his ravishingly rich poetry? Do people who love Homer need to be blind? Those comments strike me as both naïve and sexist, but that is not the point of this blog.

Today, I realized in a simple, clean epiphany that was far from surprising or unexpected—Plath showed me that we can use words to unhinge the meaning from the experience and slam the page with truth.

She showed me that nothing is off limits.

She showed me that what is real has a place in writing. And real is found in the world outside us but also the world inside us.

Of course, other poets could have taught me this, but she is the one I found at the moment when I was open and vulnerable to awakening.

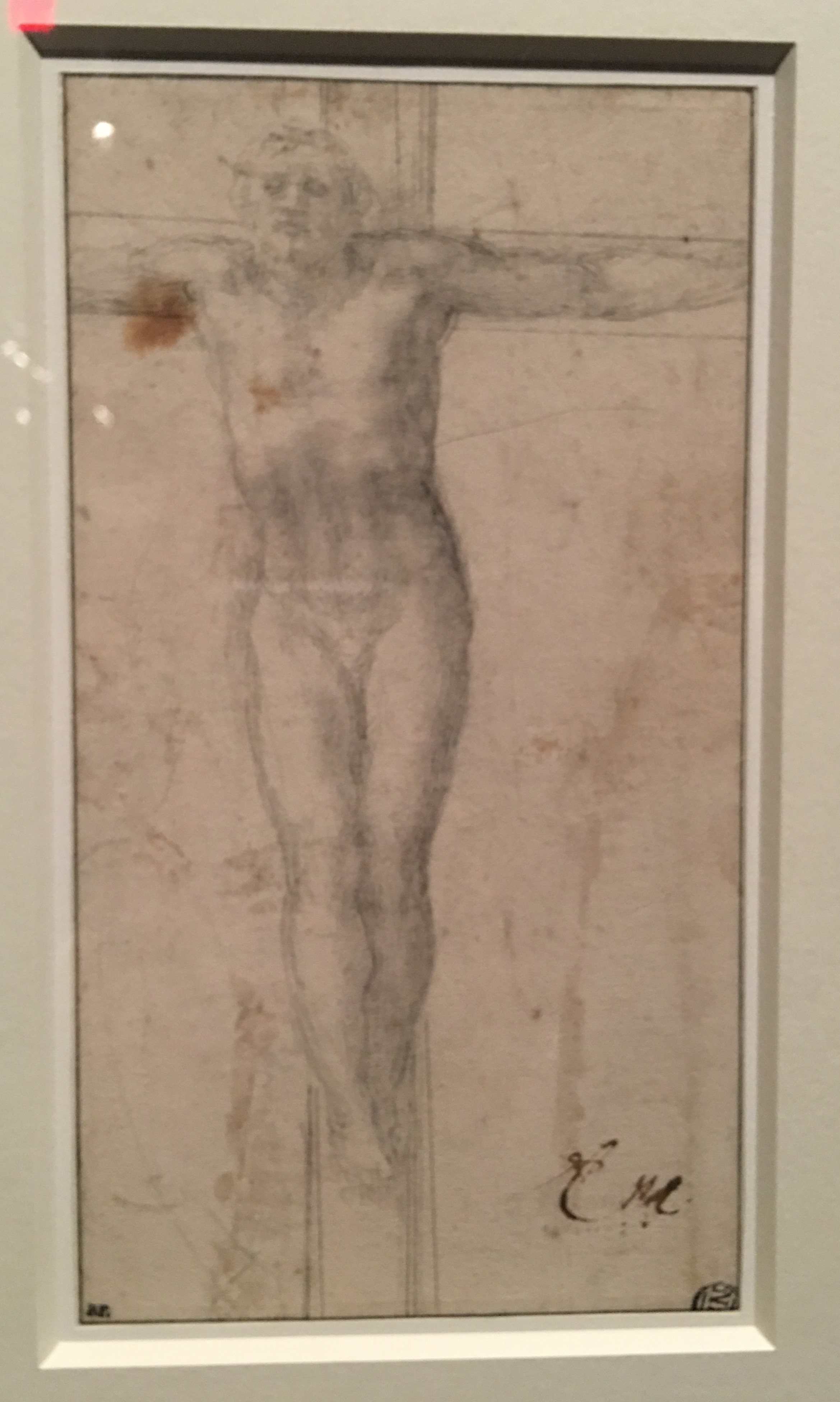

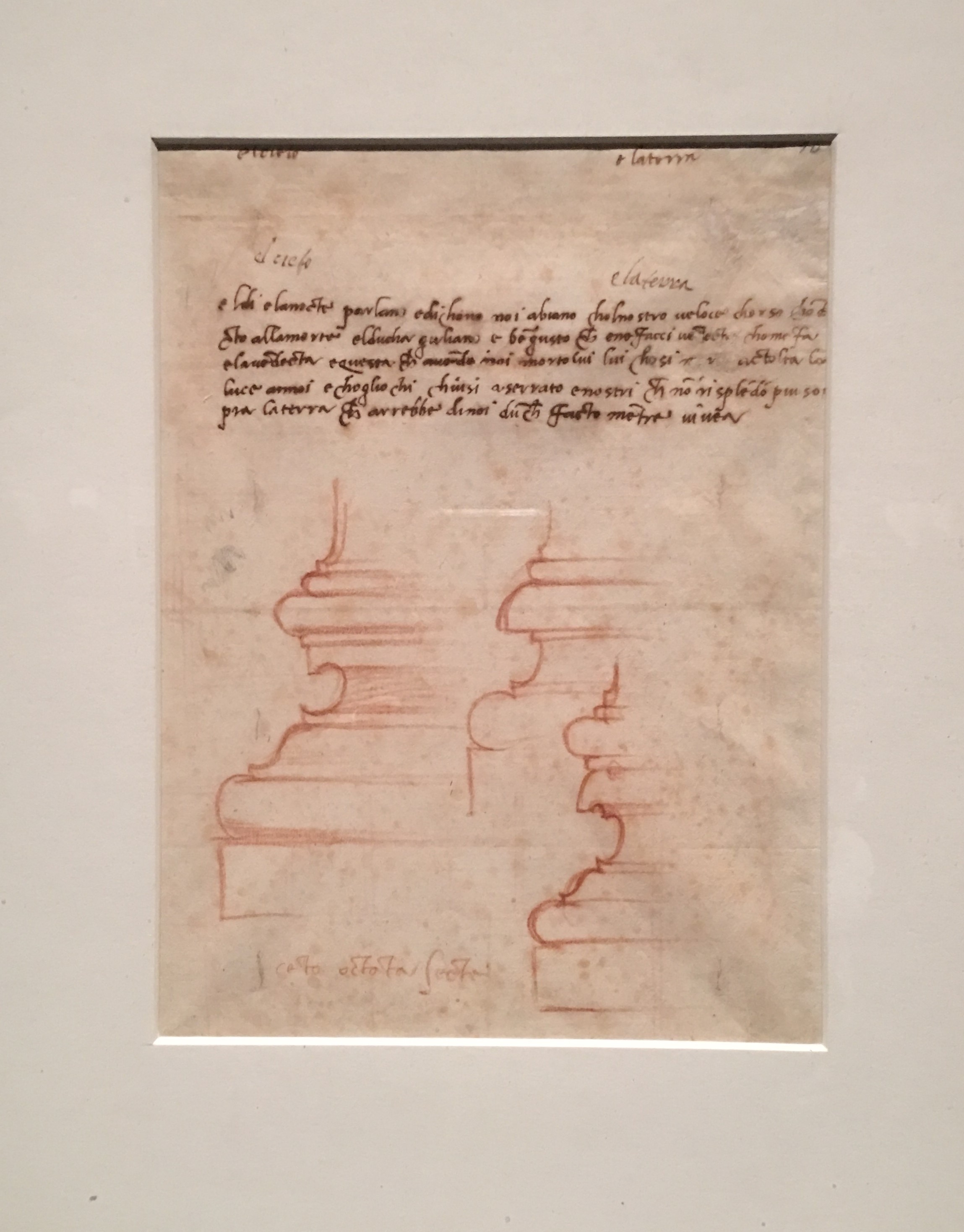

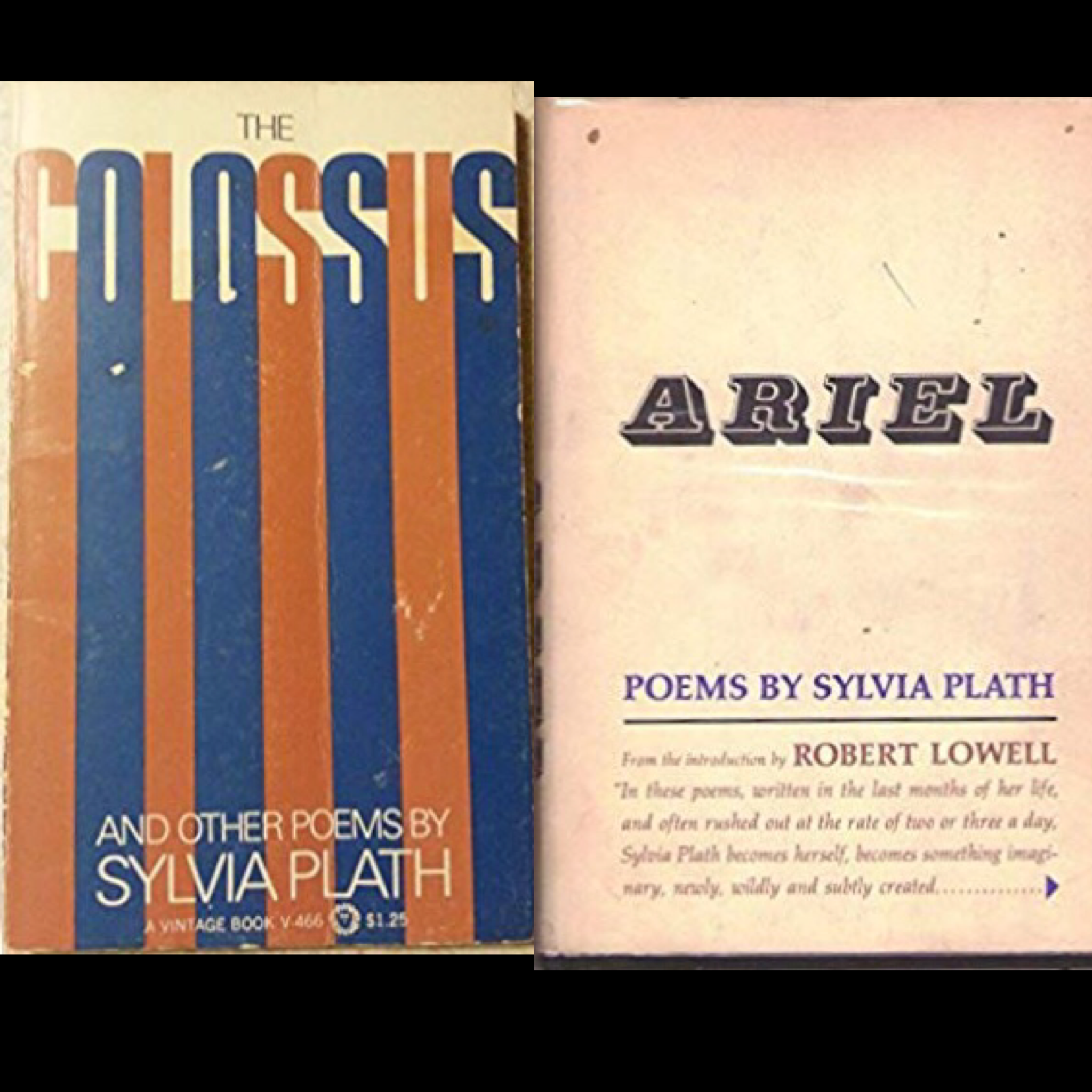

I have owned The Colossus and Other Poems and Ariel for 47 years. They are on loan to my poet daughter at the moment. I am sad about that today as I long to leaf through them. Though Colossus came out in 1960, months after I was born, and Ariel in 1965, after her death, my editions are: Colossus 1968 edition Vintage Books, and Ariel 1966 edition Harper and Row—pictured above.

But I digress.

Her posthumous book is the one that now, reading many of its poems online, I realize with some mild surprise, I must have read hundreds of times, so ingrained are the words in my mind.

Like so many very young aspiring writers, my natural talent with words was hidden under bushels of cliché and “shoulds” when I was 12, 13, 14. The stuff I wrote at 6 and 7 was far more real. Plath was the bitch slap I needed… and so much more.

In “Lady Lazarus” Plath scorchingly writes of her near deaths, one by chance and one by her own hand, adds raw layers of stunning images—her, curled up under the house, trying to die while underground critters came to rest upon her (“I meant / To last it out and not come back at all. / I rocked shut / As a seashell. / They had to call and call / And pick the worms off me like sticky pearls.”)—and references to Nazi doctors (“So, so, Herr Doktor. / So, Herr Enemy. / I am your opus, / I am your valuable / The pure gold baby, / That melts to a shriek.”), carnivals (where she is the attraction: “There is a charge / For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge / For the hearing of my heart– / It really goes.”), and so much more as she rises again and again from death (“What a trash, / To annihilate each decade.”).

I read these words, at 15 and 16, knowing that she did not rise again, the next time she tried. I knew this voice was silenced forever and it grieved me. I cried real tears for her, and for me, for all we both lost.

“Daddy” was another poem that sank into my bones. I did not know, till then, that we could write such forbidden things. That we had permission to speak truth to power. That fear need not demand silence if proclaiming these truths would have meaning. If not to anyone else, at least to the writer herself. I was scandalized, thrilled by her scorn for the Nazi beekeeping father who held such sway over her life:

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You——

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

But not only that—the bold zero-fucks-given way Plath just went there. This may seem like no biggie nowadays. People write from depths that were off limits 40, 50 years ago. I believe Plath’s unrepentant, slicing honesty and the devastating perfection of her language helped pave the way for every writer since. And that is with her husband’s horrible interference, now thankfully undone in more recent editions.

The Bell Jar was an amazing book and of course I read it. But only once. I am a writer of prose, not poetry, and yet it was her poems that called to me again and again. I have never read any book as many times as I’ve read Ariel. Why? I asked myself that today for the first time.

It freed me. It blew open my mind to possibility. I did not try to act on that possibility till several years later, in my fiction, but the seed was sown, permission given.

And I adore her because she did not need permission. She was a trailblazer who, despite suffering from mental illness I cannot fathom, wrote. She wrote real. She wrote genius. She wrote pain. She wrote her own ugliness. Her strength. Her tragic flaws. Her own unmatched, shocking beauty.

Her words were an incision, clean and kind, into me. Thank you, Sylvia Plath.