The following is my imagined, fleshed-out story of something my mother told me about many times–her relationship with a woman in her town named Mrs. Myers.

Lee Park’s life embodied a duality. A girl born into poverty to Viola, a mother who was strong and capable, but a religious fanatic. Viola was often so seized by the spirit that she stopped functioning and spoke to Jesus while blockading herself behind a door. Lester, her father, was jolly and loving, an alcoholic, a jack of all trades. Beloved by his children, but sometimes the reason for their hunger and penury. My mother and her brothers would be tasked with searching the local bars for him and bringing him home to sober up so he could go to work the next day.

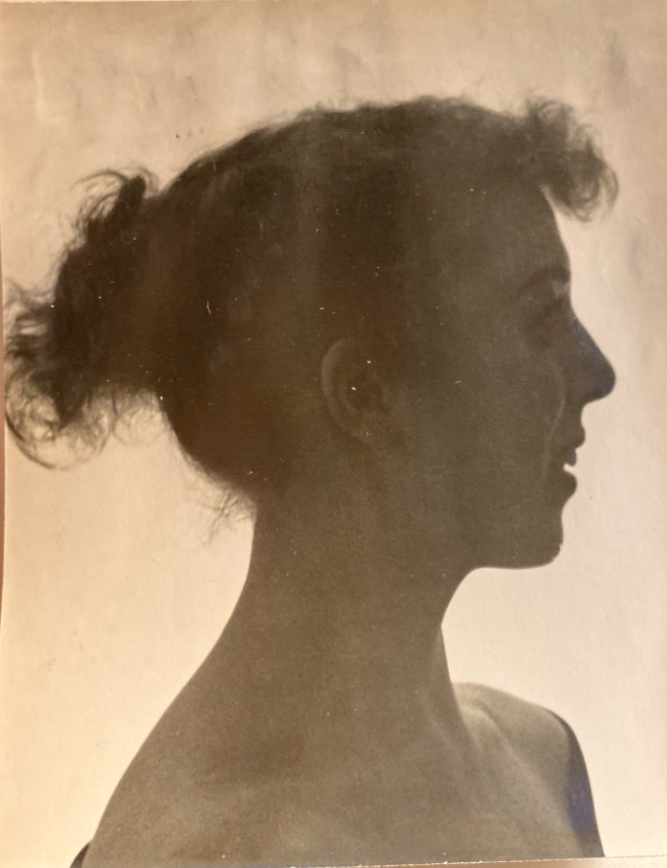

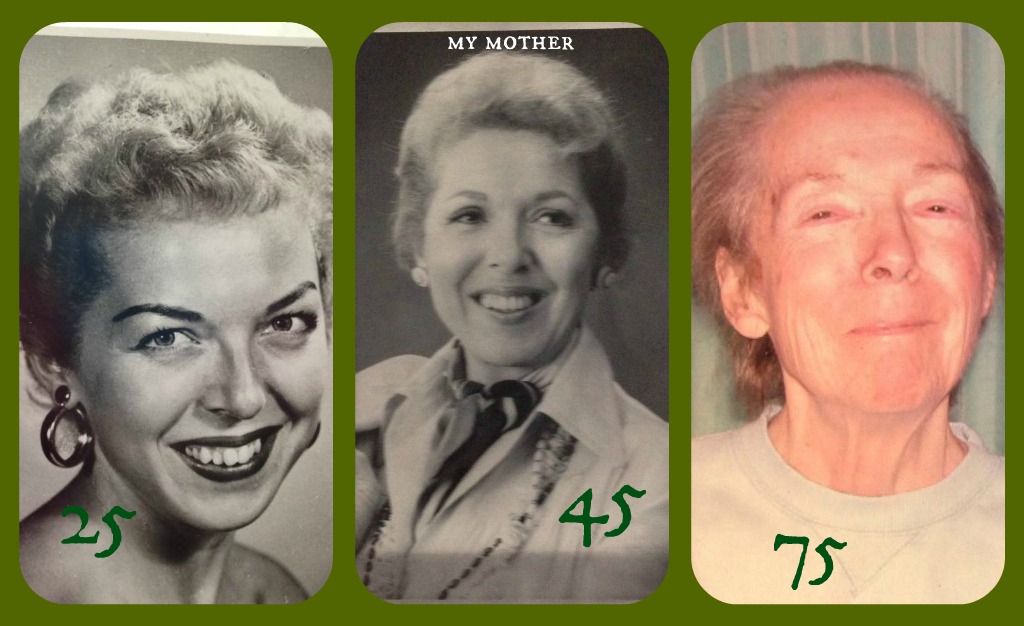

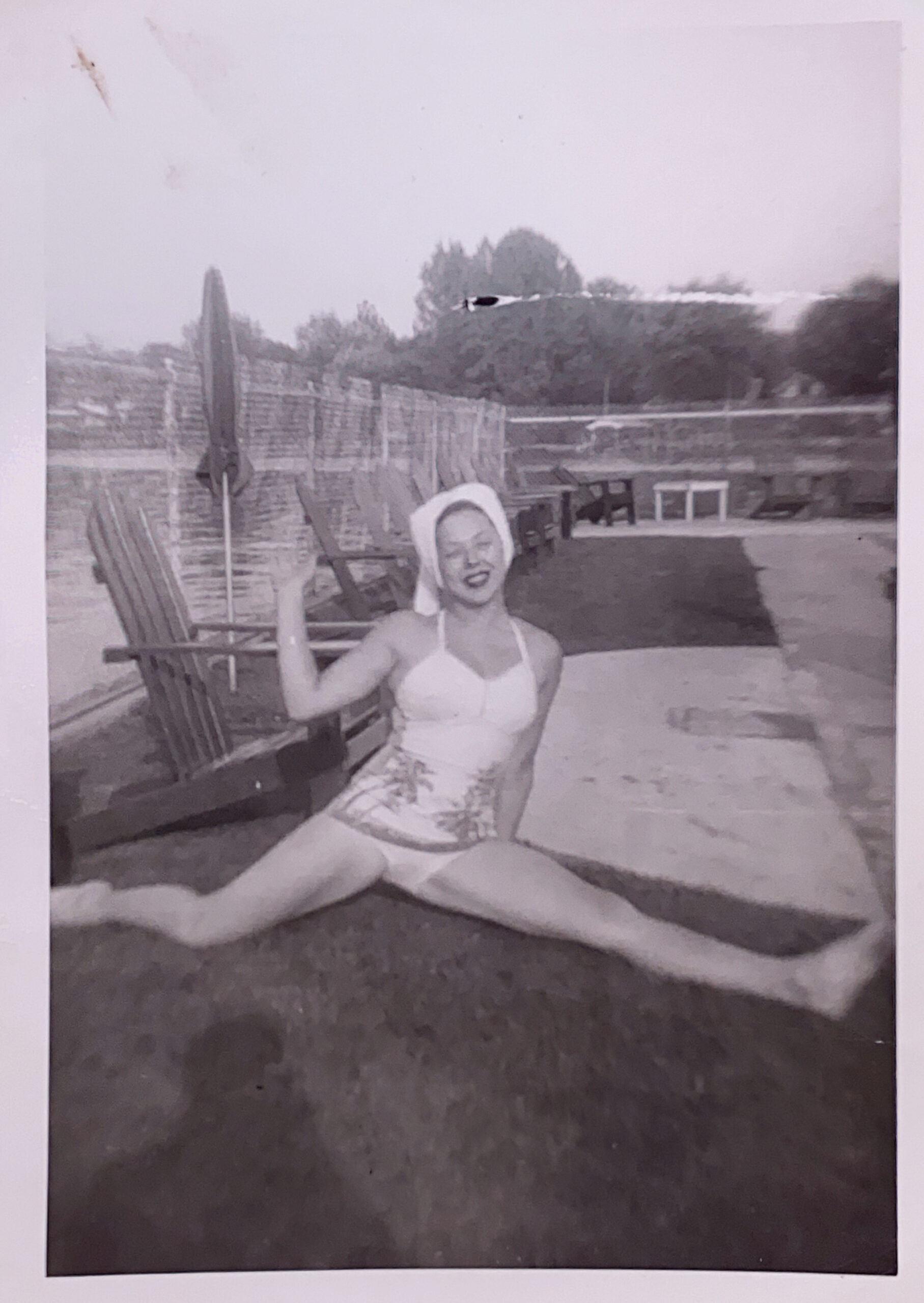

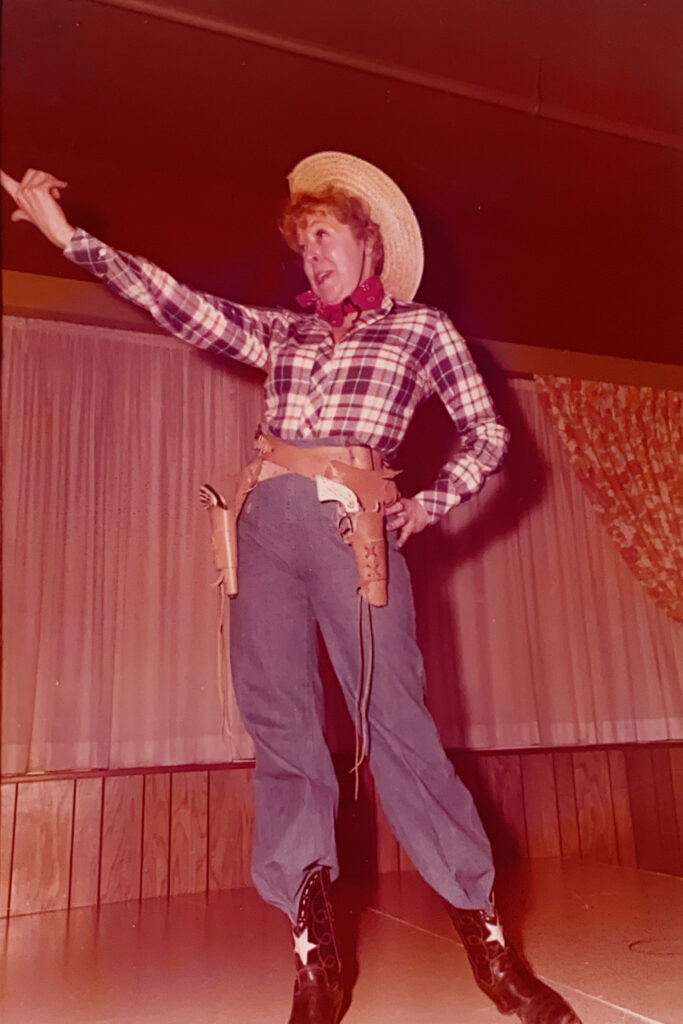

Photos of her as a little girl show a crooked toothed smile, a halo of golden curls, and, as she grew, her sense of her own power shone through. Even as a teenager she stood tall and straight, or spine curved backwards into a capital C, one knee raised high, as she held her baton high in the air, a skinny drum majorette with big plans. In nearly all her photos she is grinning wide, despite being self-conscious about her crooked teeth. There was unmistakable joy in her face—an exuberance born of confidence and big dreams. I don’t know if, during my lifetime, I ever saw my mother that way–completely unfiltered. Maybe sometimes, when we were alone, and found ourselves laughing completely out of control. Rare, precious moments of that exuberance left over from the time when I never knew her, the time before she created herself, which was long before she lost herself.

My mother literally invented herself from scratch, and it started young.

**************************

There was a woman named Mrs. Myers who lived in Granville, or Hebron, or Buckeye Lake, or wherever they lived when my mother was a young girl of 6. Mrs. Myers had a lovely home with two stories and lots of windows, a grand covered porch, and at least one servant.

I never really knew how small Norma Lee met Mrs. Myers, but I know that my mother chose this cultured, elegant woman to be her personal life coach, sometime in the mid-1930s. My mother knew even then that she needed to learn things, be exposed to ideas and cultivate habits that would serve her in the future.

Mrs. Myers taught small Lee:

- How to pour and serve tea

- How to walk down a stairway and keep her head perfectly still

- How to cross her legs at the ankles

- How to pronounce words so she did not sound “country” or ignorant

- How to modulate her voice in a variety of settings and circumstances

Knowing how to pour tea perhaps never came in handy, but the overall idea that being polished and knowing how to show up in the world to get ahead and meet the “right” people—that came in handy and even so young, Lee knew what she needed to learn when the right teacher crossed her path.

One day in the spring of 1935, a little girl sat on a low wall, waiting for her mother to come out of the general store. Her name was Norma Lea. Her hair seemed to float around her face like cotton floss and though her knees were grubby, her hands were clean, and she wore navy blue buckle-shoes over bare feet.

A big two-toned car pulled up to the sidewalk twenty feet down the street and the driver emerged. He wore a sharp blue jacket with brass buttons and a brimmed cap. He walked around the car to open the back passenger door. A woman emerged. She had black hair graying at the temples and was smartly dressed in a white seersucker shirtwaist dress with a brown belt and low-heeled brown and white Oxford pumps. Little Norma Lea stared openly at this vision. The tasteful finger waves in her hair, the crisp dress, the elegant but practical shoes, and the car. Her daddy would know what kind of car that was. It was big. It had four doors and a long hood.

The woman who emerged from the car was older than Norma Lea’s mama, but looked younger somehow. The little girl realized the woman was looking at her, walking in her direction along the sidewalk. Norma Lea tucked her chin but kept watching the lady from under her eyelashes. As the woman got closer, she smiled at Norma Lea, a big easy smile, and said, “Good afternoon, young lady. I trust you are enjoying this lovely spring day?”

Norma Lea sat bolt upright. It had not occurred to her that the lady would take the slightest notice of her. Belatedly, she sprang to her feet. The woman had paused, waiting for a reply. The child walked the two feet between them and reached out to take the woman’s hand in both of hers. The woman looked both startled and charmed. “Yes Ma’am thank you. Also you are very beautiful.” Norma Lea dropped the lady’s hand and took a step back.

“What is your name, little one?”

“Norma Lea. My daddy calls me Dutch. My brother calls me Lee.”

“Well Norma Lea, my name is Mrs. Myers. It’s very nice to meet you.”

The child stared, unsure what to say.

Mrs. Myers smiled and said, “Be a good girl. Are you waiting for someone?”

Norma Lea nodded.

Mrs. Myers said, “Goodbye now,” and walked away, a little girl’s eyes burning holes in the back of her crisp white dress.

One day a few months later, at the height of steamy central Ohio summer, Norma Lea’s daddy had use of his employer’s truck to haul some lumber from the sawmill to a building lot. He told his kids that morning to wait for him at the corner at 9:00 a.m. and he’d come by and let them hop in and ride around with him for a bit. This was the height of exciting entertainment.

Her brother Frosty got the window and Norma Lea sat between him and their daddy. They drove out of town to the sawmill and Frosty, only 7, wanted to help load the long boards into the truck bed but some men came out to do that. Frosty and his sister wandered out toward the road. Across the way was a field covered in tiny yellow flowers. Frosty sprinted across the empty road, grabbed a handful of buttercups and came back to his sister. He held one under her dimpled chin and said, “Aw look at that. I guess you like butter!”

Norma Lea said, “Course I do. Everybody likes butter!”

“Well, this proves it for sure.”

Norma Lea pointed at the field of buttercups and said, “What’s over there?”

“Yellow flowers, dummy! I just fetched a bunch.”

“No, I mean over there on the other side?” They squinted. “It looks grand.”

When daddy picked them up, Norma Lea said, pointing, “Can we drive on that side of the field and see what’s there? I ain’t never been in this part of town before.”

They drove around the big square of land that held the buttercup field, a small gray barn and silo, some modest houses, an alfalfa field. When they rounded the corner onto the street way on the other side, Norma Lea deftly moved herself onto her brother’s lap so she could see out the window. Frosty just shifted so he could see too, and wrapped his left arm around her waist so she wouldn’t slide off or wiggle too much.

On their side of the wide road were big houses, set on big lots. Between one end of the long block and the other, there were only three homes. One of them was set back, with a long driveway and another, much smaller stone house set by the road. One of them was painted butter yellow and had a deep porch that wrapped around three sides. The last one was dark gray with robin’s egg blue shutters on the windows, but they were all closed. It looked like no one was home.

Lester, the children’s father, could tell they were fascinated by these rich houses. He slowed down as they passed by in silence.

That night at the kitchen table, Norma Lea could not stop talking about the three houses they had seen. “One of them had blue shutters and one of them had a porch bigger’n this whole house!” She intended to go back there soon, she announced. She had to know who lived in those houses.

“No one who wants to know you, I’ll wager,” said her mother Viola, wrapped in a brown and white apron and serving ears of fresh corn and a bowl of sliced tomatoes. A small chicken lay carved open on a plate. Ernie, the baby—well, he was almost two—sat on Norma Lea’s lap. He was a big boy, and nearly eclipsed his sister. She blew raspberries into his neck to make him laugh and she kept her arms wrapped around him until their mother said it was time for him to sit in a chair and eat.

Frosty helped his sister find the houses again. He was a whole year older and could navigate their small town marginally better than she could. It turned out it was only a 15-minute walk from their little four room house. When they got there, they strolled past the houses slowly so Norma Lea could study the details. Her favorite was the yellow one with the expansive wrap-around porch.

A week later, when no one was looking for her to watch Ernie or hang diapers on the clothesline, Norma Lea retraced the route and found herself squatting in the shade of some trees that edged the field behind her. She was across the road from her favorite of the three houses. The middle house—the one with the big porch. As she watched, a big car drove down the road and turned into its driveway. It pulled in and disappeared around the back.

A few minutes later, the front door opened and someone walked to the edge of the porch. It was a lady, with her hand above her eyes to cut the glare from the high summer sun. Norma Lea felt pretty invisible where she squatted in the dark shade. But then she wondered, “Is that lady looking at me?”

The lady was wearing a yellow skirt with wide pleats. When she moved, Normal Lea glimpsed green inside the pleats, like a secret surprise. The lady also wore a pale pistachio green bonnie blouse. Norma Lea had determined that she had not been spotted where she was, but when the lady walked down the steps and toward the edge of the sidewalk, Norma Lea felt a brief panic. She stood up suddenly from her squat, lowered her head, and walked back the way she’d come. Something made her stop.

She turned around and saw the lady walking across the quiet street. It was the same lady she met that day waiting for her mother. Mrs. Myers!

“Norma Lea, is that you?”

Before the child knew what had happened, she was sitting in a cushioned wicker chair on the porch and Mrs. Myers was pouring lemonade into glasses. Norma Lea could feel her heart thud inside her chest—a funny feeling. But she felt good. Her legs dangled off the edge of the big chair and she listened to Mrs. Myers talk about the weather, why lemonade was good for growing girls, and her adult son who lived in Indianapolis.

This is how I imagine the apprenticeship of Norma Lea Bauman began. She learned not to say “ain’t” and how to curtsy when meeting her elders. How to set a table, with the napkin on the left, and how to glide instead of walk, even when going downstairs. That one was tough for a bouncy little girl, but she was an earnest and committed student. Years later, she taught me the same thing, coaching me down the wide central stairs of the Metropolitan Museum, keeping her eye on the top of my head. “It’s all in the knees,” she coached, in Mrs. Myers’ voice.